|

Willis Lamm 12-6-14

|

|

|

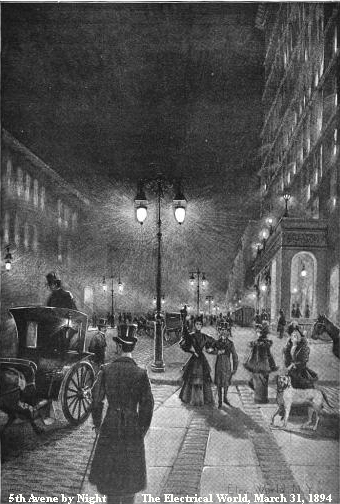

In order to understand how early street light systems worked, it helps to understand the technology of the time. In the late 1800s, electricity started to replace gas, oil and gasoline powered street lamps. However engineers and designers had to resolve how to deliver sufficient electrical current to these new devices and how to produce sufficient illumination.

The electric light bulb was still in its infancy and the amount of light produced by light bulbs was relatively low. As a result, most electric street lighting was provided by arc lamps. The concept of the arc lamp was pretty simple. Inside the lamp two rods called electrodes, primarily consisting of carbon, were placed with their ends a short distance apart. When sufficient current was supplied, a continuous spark was generated between the electrodes, much like with present day arc welders. The light produced was harsh and the lamps were a challenge to maintain, but their illumination was brilliant and arc lamps were in use throughout the world well into the 1900s. (For an additional discussion on arc lamps, please visit Understanding Arc Lamps.) The devices for delivering high intensity light were thus available in the late 19th century, however there were still the challenges involving bringing sufficient electrical current to these lamps to be overcome. |

|

|

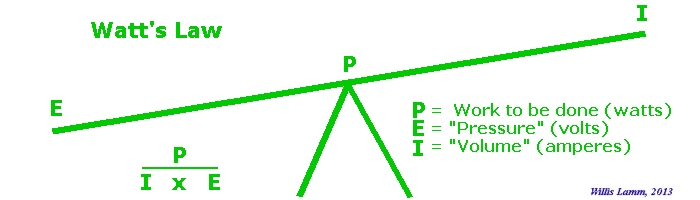

Arc lamps generally operated at around 50 volts DC and they each drew several amperes of current in order to maintain the arc. Lower voltages at high amperage would not efficiently travel great distances unless exceptionally large electrical cables were provided. To understand why this problem exists we simply need to look at some familiar items. For example, a battery cable for a car, delivering 12 volts at high amperage, is fairly large. Conversely the cord for a space heater, delivering 120 volts at a much lower amperage, is much smaller.

We need both voltage and amperage to produce useful working power. Using water in a hose as a simple comparison, voltage is akin to pressure while amperage is akin to volume. At high pressures you can get a specific quantity of water down a small hose. At very low pressure, you would need a much larger hose in order to deliver the same amount of water. In reality electricity at all voltages travels at the speed of light while water varies in speed according to pressure, but the relationship to the size of the conductor (wire) needed is the point I am making. If we view voltage and amperage as opposite ends of a teeter totter, as voltage decreases, the amount of amperage needed to do the same work increases, and vice-versa.

The problem was that arc lamps operated at relatively low voltages. Individual photocontrols had not been invented in order to turn each individual lamp on at dusk. Arc lamps were installed for miles around and would either require a separate switch on each lamp that someone would have to operate twice a day, or they needed some kind of centralized circuit to power them only at night. But the size cable needed to power such lights for any distance was prohibitive. The solution was actually relatively simple. The lamps were wired in series on high voltage circuits that originated from the electrical utility's central station. Additional Information Sheets: |