Part Two

As incandescent lamps became capable of producing more brilliant light, engineers went in a number of directions to more efficiently direct this light and reduce glare. Street lighting could be made to be more economical, so a great effort was made to make the most of the light produced. Open reflectors gave way to diffusing globes, that gave way to refracting globes having prismatic elements that "bent" and focused the light produced by the lamp. Improved reflectors reduced glare and unwanted "side splash" that could be annoying to motorists or nearby sleeping residents. These issues are more thoroughly covered in the feature, Street Light Designs.

|

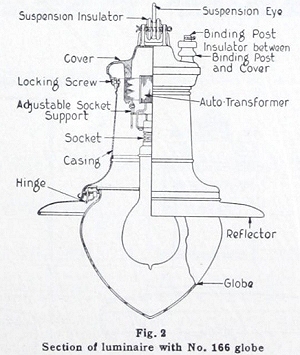

Their first approach involved the use of autotransformers. The series circuit ran across the primary winding of each autotransformer and the lamp, regardless of its type, would be supplied by the secondary winding. If the bulb failed, the primary winding would still carry the circuit's current and the regulator would adjust for the change in load. There were two disadvantages in using autotransformers. There was some loss in electrical efficiency when circuits ran through autotransformers. Also there was a tendency for autotransformers to generate significant radio interference when a lamp failed. |

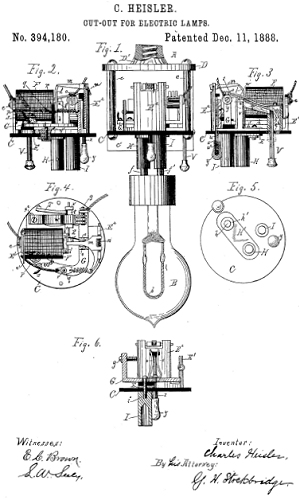

A logical approach to keeping series circuits alive when a lamp failed was the magnetic cutout. A magnetic cutout was basically a high resistance electromagnet that was wired in shunt (parallel) with its associated lamp. When the lamp failed, the voltage would pass through the electromagnet's coil, pulling closed a kind of toggle switch. The switch would stay closed until a lineman repaired or replaced the lamp and manually reset the cutout. These devices worked efficiently with arc lamps but engineers soon found problems associated with incandescent lamps. Series lamps generally operated at less than 50 volts. However if the circuit opened, the regulator could produce several thousand volts in an attempt to bring the circuit up to its designed operating amperage. (Please see Understanding Series Circuits for a detailed explanation of this phenomenon.) When the voltage at the failed lamp ran high, and if the cutout did not operate quickly enough, there could be a virtual lightning storm inside the failed lamp bulb that could occasionally melt down the luminaire's socket and internal components. Inventors worked to produce smaller and faster acting magnetic cutouts, however except for lamps that had autotransformers, the magnetic cutouts gave way to faster acting film cutouts. Nonetheless it was discovered that lamps that ran off of isolation transformers that also had cutouts resolved the radio interference problem. Isolation transformers kept the voltage from running critically high at the lamp when it failed which made the use of resettable magnetic cutouts feasible for those installations. |

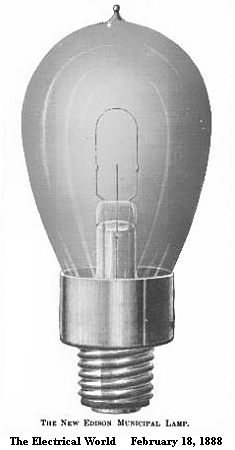

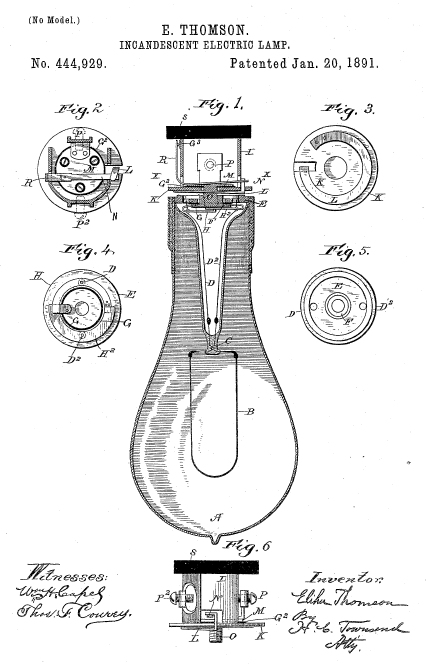

To resolve the arcing and meltdown issue, in the late 1880s inventors developed self-shunting lamp bulbs. The filament leads were separated only by a thin film of insulating material. Once the bulb failed, an arc would pass through the insulating material fusing the leads together and maintaining continuity across the failed lamp. Socket inserts were also designed that used a similar principle. The primary drawback to these designs involved the fact that burned out lamps could not be replaced when the circuit was active unless in addition there was some kind of manual cut-out that would bypass the lamp. Otherwise when the lineman removed the bulb, the entire string would go dark. With the bulb removed, line voltage would spike and there could be a significant arc flash when the bulb was screwed back in. So linemen either had to remember which lamps had gone bad and replace them at a later time when the circuit was off, or there had to be a means to cut-out and bypass the lamp that was being changed. However with circuits where the lamps were shunted by autotransformers, lamp and socket film cutouts were effective in resolving the radio noise problem, particularly in luminaires where there was insufficient space to install a magnetic cutout.

Thomson film cutout socket in a Holophane luminaire.

|

Removable Jones socket in a Line Material Co. luminaire.

|

As explained in Part One, series circuits, while efficient, had one significant drawback. By their very nature, if a lamp failed anywhere along the series string the entire circuit would go dark. Some means was necessary to shunt (carry voltage around) a failed lamp. Engineers and inventors were well aware of this issue and attempted to address it in a number of ways.

As explained in Part One, series circuits, while efficient, had one significant drawback. By their very nature, if a lamp failed anywhere along the series string the entire circuit would go dark. Some means was necessary to shunt (carry voltage around) a failed lamp. Engineers and inventors were well aware of this issue and attempted to address it in a number of ways.

Lamps were screwed into the the removable socket. A film cutout was inserted between the blades of the socket's bayonet that kept current from conducting between the two blades while the lamp was functioning, but would melt when the lamp failed and voltage spiked.

Lamps were screwed into the the removable socket. A film cutout was inserted between the blades of the socket's bayonet that kept current from conducting between the two blades while the lamp was functioning, but would melt when the lamp failed and voltage spiked.