The history of the wild horses living on the Currituck Outer Banks begins more than 400 years ago. In the early 1500s, Spaniards explored coastal North Carolina. They brought with them horses that were raised in the Spanish colonies which are now Puerto Rico. Originating from Spanish and Portuguese Barb stock, these choice mounts were bred for their stamina, size, temperament, ease of gait, longevity and their ability to survive and work in a sandy, harsh environment. It is accepted that Barb horses (after the Barbary Coast of northern Africa) are related to Arabian horses found in the sandy deserts of the Arabian peninsula. Along with other livestock including cattle, sheep and pigs, the horses were transported by being harnessed on the decks of Spanish ships. Because of the lack of deep harbors in North Carolina, some of the livestock made the final leg of the journey by swimming ashore. Native Americans, of course, inhabited much of the areas the Spanish (and later the English) explored and settled. The relationship between the native and non-native cultures was not enhanced by the sale of Indians into slavery. Many were "exported" to the West Indies through Charleston, South Carolina. According to Dale Burrus, senior Inspector for the Spanish Mustang Registry, Indian revolts forced the Spaniards "to flee to stronger Spanish holdings in Florida, leaving behind all their livestock." When Richard Grenville led expeditions to America on behalf of Sir Walter Raleigh, he to stopped in the West Indies to trade with the Spanish colonists - even though England and Spain were actually at war during part of this time. For many years it was difficult to put together the needed information concerning the early exploration and colonization carried on by Raleigh's ships, especially that regarding their exploits and trading with the West Indies. But in 1955 the Hakluyt Society published two volumes of considerable information, most of it gathered in archives in England and Spain. We now know, for example, that according to Spanish documentation on June 6, 1585, Grenville purchased make horses and mares (with saddles and bridles), cows, bulls, sheep and swine for the colony. We also know that Grenville made voyages to Raleigh's colony on Roanoke Island during the springs of 1584, 1585, 1586, 1587 and 1590. English historian John Lawson explored and documented his findings in southeastern North Carolina from 1700 to 1711. He described the horses he encountered as "well shaped and swift." There were no horses native to North America, but it is known that the Indians eventually adopted them. Of the horses tended by the Indians which Lawson observed, he reported that they were well treated and fed maize. According to Lawson, these Indians did not ride their horses, "never making any farther use of him than to fetch home a deer." By 1856 when agriculturist and editor Edmund Ruffin visited the Outer Banks, the Indians had been displaced or absorbed, and the new residents used the horses for a variety of tasks. Ruffin wrote, "Twice a year on the Banks, the stock owners hold a wild horse penning." He also claimed that all the horses living on the reef (the barrier island), and many on the mainland farms, were descendants of these previously wild "banks horses." The horses were employed not only for transportation, but also by fishermen to haul their nets out of the ocean. They were sometimes used by the Life-Saving Service surfmen as they made their patrols along the beach. A banker horse participated in the rescue of the Priscilla in 1899. The Wright Brothers made use of horse and card in Kill Devil Hills. As machinery replaced horses for these chores, they ceased to play an important role, other than legendary, in the lives of the residents of the Outer Banks. Also legendary is the isolation of the Outer Banks. Although there was considerable maritime traffic, a bridge finally linking the Nags Head beaches to the Dare County mainland (via Roanoke Island) was not built until 1958. A 1938 Federal stock law (designed to protect the new WPA dune plantings from grazing animals in such places as Hatteras Island) was obviously overlooked on the very undeveloped banks of Currituck County. Let's remember just how recently this area has changed after centuries of natural isolation. For example, unlike other remote but more popular areas of the barrier islands, the Currituck Outer Banks was not connected to line- distributed electricity until the 1950s. Before 1984 there was not a road to Corolla; a visitor (and there weren't many) had to come by way of a winding lane through the soft sand or on the firmer sand of the beach at low tide. Even after the road was completed, a guard gate allowed only the few landowners and their guests to pass. It is said that there were only nineteen residents who occasionally would see the wild horses which kept mainly to the marshes and maritime forests. In their nomadic travels to forage for food, a herd of horses could sometimes be found at the Whalehead Club. Before development, the grounds there offered one of the few grazing areas of cultivated grass. Such isolation before paved roads and subdivisions is difficult to imagine; and it all has been transformed in less than 15 years! Naturally the roads brought more auto traffic and in 1989, one car accident caused the deaths of three pregnant mares. After this tragedy, 50 or so residents of the area met at the local firehouse and the Corolla Wild Horse Fund was established. By the end of the year, the County Commissioners had declared the Currituck Outer Banks a sanctuary for the wild horses, making it illegal to harm, approach, feed or kill them. But with so much development and so many daily visitors, the ordinance was not enforceable. Natural vegetation was replaced by lush sod and green lawns which proved far tastier to the horses than the marsh and flatland grasses which had sustained them for so long. A particular problem was the feeding of the horses from tourists' cars which conditioned the horses to approach vehicles and the roads. "Ococo" and "Viento"

|

|

WANT MORE INFORMATION? WANT TO HELP? |

Check out the Corolla Wild Horse website:

- Links to lots of information, how to help, how to "adopt" a Corolla wild horse.

Tours are available to experience the Corolla Wild Horses at Wild Horse Adventure Tours

We are not affiliated with Wild Horse Adventure Tours.

We have listed them as perhaps the best way our web site visitors can experience the Corolla Wild Horses.

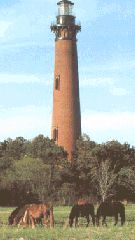

The Currituck National Wildlife Refuge is located on the north

end of Corolla Island, a few miles from the Currituck Beach

Lighthouse. Here endangered plants, wild boar and Corolla's

famous wild horses have a safe 1,800 acre haven. The animals

here are separated from more modern life by a four foot fence

which extends from the ocean to the interior "sound". People can

enter the refuge on foot or via 4-wheel drive vehicles over a

cattle guard.

The Currituck National Wildlife Refuge is located on the north

end of Corolla Island, a few miles from the Currituck Beach

Lighthouse. Here endangered plants, wild boar and Corolla's

famous wild horses have a safe 1,800 acre haven. The animals

here are separated from more modern life by a four foot fence

which extends from the ocean to the interior "sound". People can

enter the refuge on foot or via 4-wheel drive vehicles over a

cattle guard.