Gentling Wild Horses,

|

|

I can relate to the concept that a wild horse brought into the human environment must feel like a stranger in a strange land. Years ago as a young man I worked on a technical project for about 6 months in a foreign country. I worked directly for "nationals," not Americans. I didn't speak the language nor understand all the social rules. Even though I was

motivated by good money and a sense of adventure, adjusting to this temporary lifestyle had more than enough stressful moments.

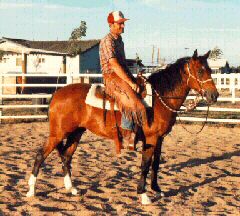

I soon discovered that in order to "survive" comfortably, I had to develop professional relationships with those people who could communicate with me. Until my ability to converse in their native tongue improved, I felt extremely dependent upon those with whom I could actually communicate. As I started getting serious about horse training, it became clear to me that I would be much more effective if I could "speak" the language of horses; expressing myself in terms which they naturally understood, and I needed to also be able to "read" their expressions. I soon found that by doing this, the horses learned much more quickly. Once they discovered that I would "listen" to them, they seemed to develop much more openness in expressing themselves and developed confidence in our horse-human relationships. Over the period of time I have been working with horses I have observed that those owners and trainers who seem to have the easiest time of it are the ones who take the approach of treating a horse like a horse, trying to communicate on his level and seeing the world through his eyes. Particularly in those early stages when one is first molding the horse's behavior, such knowledge and understanding is invaluable. In 1992 I worked with the first "wild" horse I'd ever encountered, a 5 year old named "CJ." Until then I had only worked with domestic breeds and draft horses. While CJ had received some halter training at the California State Prison in Susanville, he didn't really like people and was very difficult to catch. CJ's owner brought him over to our ranch for us to gentle and start under saddle. By applying efforts toward horse communication, CJ would soon come to up me to be haltered. Before the end of the week he was saddled up and I was on his back. It never occurred to me that this wasn't the norm for adopted horses and I was surprised when the BLM volunteers expressed amazement with his progress. I just did my best to act like a dominant horse, not the 2-legged predator that I was born to be. I concentrated on sensing what CJ was thinking and feeling, usually from his expressions and his body language. If I sensed that on my approach he would step away if I made three steps toward him, I settled for taking only two. If he turned his butt towards me I would annoy him with gestures or a twirl of the halter rope. As soon as he turned to face me, I relaxed my posture and backed off a step or two. I never generated enough pressure to send him scrambling, however. Within only a few minutes he learned that things were much more comfortable if he faced me and he maintained a respectful attitude. Next I approached his left shoulder, patiently and quietly. I positioned him alongside a fence so if he started to move, I could check his forward motion by applying pressure in front of his shoulder and stop him backing up by applying pressure behind his shoulder. (By applying pressure, I mean that I gestured toward him with my hand, as if one would gently send him off. I was careful not to overdo it and cause him to bolt.) I didn't approach him menacingly nor sneakily. When I got close enough to touch his shoulder, I resisted the temptation and instead backed off a couple of steps. If CJ turned his head toward me curiously, then I extended my outstretched hand, palm down and fingers slightly bent, emulating a horse nose, and let him sniff it. I backed away and approached him several times more before very quietly reaching my right arm over his neck slipping on the halter. He twitched a couple of times during this operation but stood very still. I gave him a few gentle scratches on his withers, then slipped the halter back off and left for the evening. The next day we repeated the exercise. CJ Relaxed much more quickly than he did during the first day. I quietly put the halter on and off a few times, then quit for the day. On the third day I modified the routine slightly. I approached CJ and stopped a few feet away from his shoulder. When he looked at me, I took one step backwards. When he looked away, I took one step forward. After a few times at this I stepped slightly toward CJ's rump. He pinned his ears. looked straight ahead and started to walk off. As soon as he shifted his weight forward to leave I took one step back. He stopped and turned to look at me. I repeated this drill a few times and pretty soon he would actually face me when I stepped back. I walked up to him, gave him a couple of scratches on the withers. I then left for several minutes, returned, haltered him up and we went out to the round corral. About 45 minutes later he was saddled up and I was quietly on top. The purpose of conveying this information is that there are certain approaches, applied with appropriate intensities, which work well with horses. Each horse is different. One may be more or less sensitive or may be more or less self confident. Even age can make a difference in behavior and how much stimulation a horse can tolerate. However, all horses are social animals. They are all looking for a trustworthy leader. They want to know where they rank in the social structure. If you set yourself up in the mind of the horse as his leader, he'll generally work his heart out for you. When two horses are introduced to each other, they generally go through a ritual to establish which one is dominant. The more dominant horse will cause the less dominant horse to move away. He can also stop and turn the lesser horse at will. Since CJ was already naturally wary of, and would move away from humans, the secret was to apply a "soft touch" to my movements; barely cause him to move or stop or turn. Once he realized he wasn't being chased, he assumed the behavior of a submissive, or follower horse and it was my ability to maintain and exploit that connection which allowed me to direct CJ's following instinct into a behavior which I desired. If you try this approach, you will find, particularly at first, that you sometimes lose this connection, or "bubble" as some horsemen like to call it. If you pop the bubble, just stay relaxed, get your connection going again and try not to repeat the mistake you made which caused things to break down. As long as you don't get upset, the horse usually won't get upset either. The remainder of early training was completed in a round corral. I don't like to train in a horse's paddock as I respect that area as his private, quiet space. Except for the necessity of teaching him to be respectful of human contact and to come up to be haltered, his time in his paddock is his own. We use a round corral for early training for several reasons, the foremost being safety. If the horse breaks and runs, he can travel in a circle. There are no sharp corners for him to run into where he might opt to jump a fence. He also can't feel trapped in a corner whereupon he might panic, turn and charge over the top of me to get away. For the purposes of control and training, I can set up whatever distance or closeness I need by either staying in the center of the circle or venturing out toward him. Even if he breaks into a dead run, I can "stay alongside" him since my orbit covers much less distance than his. Since I'm on the inside and he's on the outside covering a lot more ground, he perceives me as being much more athletic than I really am. I can "overtake" him easily, so no matter how fast he runs, he can't outrun me. Therefore he has to negotiate a peaceful arrangement of leader and follower, which I politely arrange as soon as I sense that he is asking me if we can get along. (Round corral tips will be posted shortly.) If you don't have a round corral, securely placing 4x8 sheets of plywood upright (long end up) in the corners of a square pen will help reduce the problems of square corners. Just be careful not to exert too much pressure on the horse when he is headed toward one of these modified corners. He could still build up too much speed for the corner and roll back out unpredictably. Livestock and circles When we developed the Wild Horse Workshops in the late 1990s and 2000s, we followed some of the principles taught by Dr. Temple Grandin. We found that horses we worked with were disturbed by sharp variations in light and dark, such as the shadow lines produced by corral panels when the sun is at a low angle. We also found that horses tended to stay calmer when moved in a circle. If a horse became frustrated, a roughly circular "walkabout" would usually reduce stress. Our most signifant finding in this regard involved horses that had a "stress avalanche" and appeared to go mindlessly A.D.D. If we had to move a horse in a panicked state, even from a square pen, several members spread apart walking calmly the same direction in a circle nearly always calmed the horse within a few seconds, and in most instances one of us was able to approach, halter the horse, and lead it where we needed it to go. In situations involving any highly stressed animal, it is critical that handlers constantly evaluate their approaches. If they are not demonstratively calming the horse, then it is time to back out and consider a modified approach. |

Horses are social by nature

|

| SOME COMMENTS REGARDING COMMUNICATION |

Any effective communication is a two way process. Even radio and television broadcasters undertake surveys, polls, etc., to determine how well they are doing. Your horse will be more interested in your attempts at communicating if he thinks you are listening.

So, how do you "listen" to your horse? I was going to write a couple of paragraphs on this subject but 6 year old Ellen Harrison summed it up in two sentences of a child's simple logic.

"You know it's funny how when you listen to people you listen with your ears. When you listen to horses you have to listen with your whole body." ... 'Nuff said.

Horses think in pictures (images). Thus when I'm trying to work through a problem, I break it down into mental pictures and I have much better success. Deanna Akin takes it even farther than that. She writes that she actually leads her horse, step by step, through the process... even drawing the patterns in the dirt with a stick. She says it keeps her horses curious and they seem to do well with the new maneuvers. (You can bet that generating curiosity in the horse before training certainly "primes the pump")

Added note: At the workshops we tried the drawing on the ground with a stick or crop. Strokes that move away from horses generally do peak their curiosity, and we have added the technique to our "stress reliever" toolbox.

In summation, I'm not here to suggest that what is going on is telepathy at work. Maybe it's just that through imaging we get better perspective as to how our horses view things and it generates some subtle but important changes in our approaches and mannerisms. Perhaps we feel (or appear) less tense and more thoughtful and that makes our horses more comfortable. Maybe it's a little bit of all of the above. All that really matters to the horse and to those of us who try imaging is that it works.

Notwithstanding the various approaches that we use, the success we achieved in the saddle was directly proportionate to the success we gained in preparation "on the ground".

| SPECIFIC GENTLING APPROACHES |

The Bamboo Pole Method

Clicker Training

Rope Halters and Leads

Open Training & Learn-Learn Situations

Understanding the Lick / Chew Reflex in Horses

| OTHER USEFUL LINKS |

"Gentling Wild Horses- 101"

Importance of Ground Schooling

Working With a Flag

Filly's First Saddle

"Busting" Common Horse Myths

Case Studies

Important Note: If you take on the project of developing an untrained horse, everybody will want to give you advice. Don't act on any advice, including the ideas offered in this site, unless it makes sense to you and fits your individual situation. Your abilities and the sensitivities of your horse(s) may differ from the examples given. Be alert and rational with your actions so neither you nor your horse will get hurt. This information is offered as illustrations of what we do and the reader must apply common sense since he or she is solely responsible for his or her actions.

Happy trails!Return to Part 1

Press "Back" to return to the page which brought you here

Go to KBR Training Section

Go to LRTC Wild Horse Mentors

Go to KBR World of Wild Horses & Burros

Go to other Wild Horse Links

Go To  KBR Horse Net

KBR Horse Net

KBR Horse Training Information, © 1997 Lamm's Kickin' Back

Ranch and Willis & Sharon Lamm. All rights reserved. Duplication of any of this material for

commercial use is prohibited without express written permission. This prohibition is

not intended to extend to personal non-commercial use, including sharing with others for

safety and learning purposes, provided this copyright notice is attached.

Email us to submit comments or request reproduction

permission.